About the Hôtel de Beauharnais

The Hôtel de Beauharnais, constructed in 1713, gained renown during the Consulate period.

In 1803, Josephine Bonaparte acquired the property for her son, Eugène de Beauharnais, and had the building renovated and decorated at great expense. At the fall of the Napoleonic Empire, it was sold to the King of Prussia and became an embassy during the nineteenth century. With its unique Consulate and Empire decor, the palace is an invaluable specimen of Parisian interior architecture. The house started as an early Regency town house designed by the architect himself, Germain Boffrand (1661-1154).

Design of the Consular and Empire periods was characterised by militaristic elements – symbols of war and victory, imperial emblems, such as the golden eagle, classical palm leaves and laurel wreaths. These symbols of power made a direct visual connection between the regime and the glory and authority of the ancient Roman emperors.The use of materials in glittering richness and color, seduces the viewer into physical enjoyment rather than rational analysis. Napoleon appointed Charles Percier (1764-1838) and Pierre-Fracois-Leonard Fontaine (1762-1853) as the official architects and designers of the Empire period and they became major exponents of the empire style.[1]

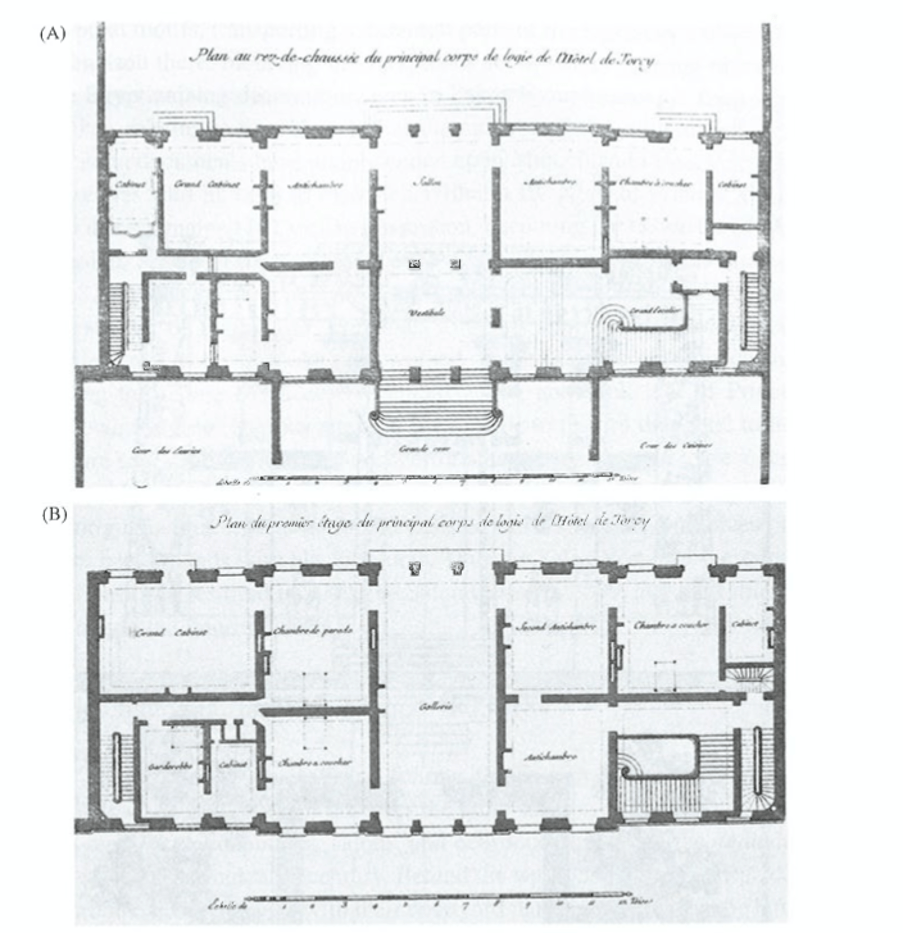

Hôtel de loiry, plans of the ground floor (a) and fìrst floor (b), Germain Boftiand, from Jean Mariette’s Architecture Française, Paris, 1727. Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris.[1]

Hôtel de loiry, plans of the ground floor (a) and fìrst floor (b), Germain Boftiand, from Jean Mariette’s Architecture Française, Paris, 1727. Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris.[2]Hôtel de loiry, plans of the ground floor (a) and fìrst floor (b), Germain Boftiand, from Jean Mariette’s Architecture Française, Paris, 1727. Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris.[2]

The Hotel de Beauharnais, Salon de Musique, with paintings attributed to the studio of Anne Girodet-Trioson, 1803-1806.

The Hotel de Beauharnais, Salon de Musique, with paintings attributed to the studio of Anne Girodet-Trioson, 1803-1806.

The Salon de Musique, on the right side of the vestibule was also newly installed for Eugène (Fig. 1.1). It is directly connected to the Salon Cerise and the Salon des Quatre Saisons. Fixed elements such as chimneys, console-tables, and boiseries offer by their color, use of materials, con- tours, and polychromy very good evidence for the style of the 1790s. Since 2000, consistent efforts have been made to retrieve the original Empire furniture, restore the fabrics and hangings, and bring back the original color schemes, which consisted of reds, greens, and blues on ochre backgrounds with black borders. [3]

The ceiling was redecorated by Hittorff for structural reasons; there is a wall covering in imitation green granite; figures of the Muses, larger than life, are depicted on the walls; birds and grotesques by Jacques Barrabant parade on the painted pilasters; below the muses are friezes with swans, festoons, and medusas. [4]

As well as military, Egyptian and Classical imagery, the Empire period also embraced opulence and imagery of love, sensuality and seduction: the swan – one of the forms the god Zeus took to seduce mortal women; the lyre – an instrument of art and seduction; and bows and arrows – the tools of Cupid.

Swans, also emblems of Venus and the adopted symbol of Josephine – were employed as armrests or as entire arms of chairs. Aspects of the myth of Cupid and Psyche were also a common theme. The butterfly symbolising both Psyche and the soul was a recurrent motif.

Inside of the Salon de Musique of The Hôtel de Beauharnais, constructed in 1713, designed by Germain Boffrand

[1] d’Olivier Berni. “Berni, d’olivier. L’hôtel de Beauharnais, 78 rue de Lille 75007 Paris,”https://www.olivierberni-interieurs.com/en/node/83. (Accessed 5 Oct 2020).

Therefore, the overall impression created by the Hôtel de Beauhamais is that of a dazzling series of interiors, in which vivid blues, red, and greens are displayed on a background of the ochre variety called “Terre d’Égyptel’ with its black borders. The glossy silk that reflects the light of day and of the many candles lit at night contrasts with the background textiles that absorb light instead of reflecting it. The newly restored interior, like the rooms at Malmaison, or the Empire apartments at Fontainebleau or Compiègne, strikes the visitor above all by the sheer effect of its brilliance. [8]

The light strikes the gilt surfaces of the bronze appliqués that are scattered over tables, beds, chairs, chimneys, or washstands; the gilt stucco moulures of friezes running along walls, ceilings, and doors dematerialise their material supports. Instead of representing the functions of columns or roofs as they would have done in previous styles, they transport the viewer into distant mythological realms.

The larger than-life paintings of the seasons and muses add to this atmosphere of illusion, since they are very similar, in the way they seem to come forward from their hazy background, to the way figures appear and take tangible form from a background of smoke and gauze in phantasma- gorias and other multimedial shows, a new theatrical genre that was born at exactly the same time as the Empire Style.

This jewellery cabinet was intended for the bedchamber of the empress Joséphine (1763–1814) in the Palais des Tuileries. The bronzes conceal locks and mechanisms allowing access to the drawers and secret compartments. The secret mechanisms were changed when the cabinet was given to the empress Marie-Louise (1791–1847) in 1810. In 1812, the jewelry case was supplemented by two further pieces from the cabinetmaker François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter, which were smaller but in the same style.[9]

Designed after a model by the architect Charles Percier (1764–1838), the cabinet has the shape of a building standing on eight vertical legs and supported by a rectangular base. Above the cornice rises a stylobate. A cassolette for perfumes stands on the base. The legs and cornice are made of purpleheart, while the interior of the cabinet, furnished with thirty drawers of the same wood (ten in each part of the body), are neither of purpleheart nor yew, but solid mahogany.[10]

The jewellery case is lavishly decorated with elements in bronze. In the center is a scene depicting the birth of the Queen of the Earth, “to whom Cupids and Goddesses hasten to bear their offerings.” Long attributed to Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751–1843), the bronzes were probably made by the Maison Jacob-Desmalter. [11]

The model for the subject in the center was the work of the sculptor Antoine-Denis Chaudet (1763–1810), whose drawings are in the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Louvre. Lastly, on each of the side doors stands a goddess turning toward the central scene. The decoration as a whole foreshadows the ornamental excess of the late nineteenth century.[12]

Cabinet made of solid mahogony and purpleheart, decorated with bronze elements, (1770-1841), designed by Francois Honore Georges Jacob Desmalter

Cabinet made of solid mahogony and purpleheart, decorated with bronze elements, (1770-1841), designed by Francois Honore Georges Jacob Desmalter

[1] Catherine Voiriot, “The empress’s jewellery cabinet”, H. 2.76m; W. 2m, D. 0.60m, The Louvre, https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/empress-s-jewelry-cabinet

Cabinet made of solid mahogony and purpleheart, decorated with bronze elements, (1770-1841), designed by Francois Honore Georges Jacob Desmalter

Materials

Above the cornice rises a stylobate. This is a base, supporting a row of columns, as described in the Greek era. The legs and cornices were made of purpleheart wood, and the interior is solid mahogany. It is ornamented with ebony, mother of pearl and gilded bronze. Just like the Arc De Triomphe, the cabinet was solid, straight and proportional, symbolic to the 1st French empire style furniture of Napoleon.

Symbolism of the butterfly

One obvious gilding on the cabinet is the butterfly. Before the Napoleon (Napoleon the 1st), butterflies were used in many forms of design, dating back to the Egyptian era, and more recently after the French empire, the Georgian era and early Victorian jewellery. Because the Napoleonic era had many Egyptian architecture and design incorporated into furniture, building and fabrics, one should note that this was very much an Egyptian influence. Excavations found in Egypt promoted interest in Egyptian jewellery and souvenirs. Butterflies represented beauty.

As mentioned in this article “two types of flies, large golden flies that symbolized “valor and tenacity in battle” and smaller flies that represented the “spirit of the deceased,” were also immortalized in seals, hieroglyphs, and jewellery.”

In the Napoleonic era, just like the swans and cupids, the butterfly symbolising both Psyche and the soul, was a recurrent motif.

Symbolism of the bronze gilded eagle

As for the Eagle, It is worth noting the symbolism of the eagles on the offered table, as in Antiquity, the eagle was the bird of Jupiter and ancient symbol of power and victory represented on the standards of the Roman legions and associated with military victories.

It is therefore fitting that the eagle, after a decree of 10th July 1804, stated that the arms of the Emperor Napoleon, `d’azur à l’aigle à l’antique d’or, empiétant un foudre du même’. Napoleon’s eagle which was very different from traditional heraldic motifs took its inspiration from the eagle used by Charlemagne. After Napoleon’s coronation as Emperor, the eagle was placed at the top of all the military standards.[14]

In my opinion, with the elaborate gilding, workmanship and hiring only the best craftsman during his reign, it makes sense that his adaptation and appropriation of the empire, Greco-Roman and Egyptian eclecticism were combined to not only reflect his empire, but it was almost as if Napoleon saw himself being reincarnated just like the ancient Egyptian rulers of Egypt.

[1] Empire style: The hotel de Beuharnais in Paris. Napoleon.org. https://www.napoleon.org/en/magazine/publications/empire-style-the-hotel-de-beauharnais-in-paris/. (Accessed 4 Oct 2020).

[2] Van Eck, Caroline et al. p.59, “The hotel de Beauharnais in Paris,” Oxford scholarship (2017): accessed 3rd Oct 2020, DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190272333.003.0003

[3] Van Eck, Caroline et al. p.65, “The hotel de Beauharnais in Paris,” Oxford scholarship (2017): accessed 3rd Oct 2020, DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190272333.003.0003

[4] Van Eck, Caroline et al. p.65, “The hotel de Beauharnais in Paris,” Oxford scholarship (2017): accessed 3rd Oct 2020, DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190272333.003.0003

[5] Van Eck, Caroline et al. p.91, “The hotel de Beauharnais in Paris,” Oxford scholarship (2017): accessed 3rd Oct 2020, DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190272333.003.0003

[6] “Interior of the salon de musique in apartment of Hortense de Beauharnais”. 1803-1810. France. Bridgemanimages.us

[7] d’Olivier Berni. “Berni, d’olivier. L’hôtel de Beauharnais, 78 rue de Lille 75007 Paris,”https://www.olivierberni-interieurs.com/en/node/83. (Accessed 5 Oct 2020).

[8] Van Eck, Caroline et al. p.91, “The hotel de Beauharnais in Paris,” Oxford scholarship (2017): accessed 3rd Oct 2020, DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190272333.003.0003

[9] Desmalter, Francois. “The empress’s jewelry cabinet.” (2008). https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/empress-s-jewelry-cabinet

[10] Desmalter, Francois. “The empress’s jewelry cabinet.” (2008). https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/empress-s-jewelry-cabinet

[11] Desmalter, Francois. “The empress’s jewelry cabinet.” (2008). https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/empress-s-jewelry-cabinet

[12] Desmalter, Francois. “The empress’s jewelry cabinet.” (2008). https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/empress-s-jewelry-cabinet

[13] Catherine Voiriot, “The empress’s jewellery cabinet”, H. 2.76m; W. 2m, D. 0.60m, The Louvre, https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/empress-s-jewelry-cabinet

[14] Grandjean, Serge, author. “A very important gilt-bronze, patinated bronze and thuyawood guéridon table by François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter”. 1966. https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2004/important-continental-furniture-and-tapestries-l04310/lot.126.html. (Accessed 4 Oct 2020).